London’s blue plaques link people of the past with the still-standing buildings they lived or worked in. It was started back in 1866 when a plaque was put up on the former house of Lord Byron – and it’s led to to 990 plaques in London, and similar schemes in cities around the country and the world. But the plaques managed by English Heritage are notoriously male dominated, with just 15% of them celebrating women. Things are even more skewed in Wandsworth, which has thirty blue plaques, twenty nine of which commemorate men. There’s no doubt that they had 29 very interesting lives – for example we’ve posted before about John Archer, commemorated by a plaque on his old house north of Clapham Junction. But it’s hard not to wonder – what about the women?

Last month, a plaque was finally unveiled for artist Marie Spartali Stillman. This is probably the start of more to come – as there’s far more to the women of Battersea than one plaque! This article, the first of a short series based on research by Jeanne Rathbone, looks at five of the many inspiring women who have lived in and around Lavender Hill.

Jeanie Nassau Senior lived in Lavender Hill in its very early days, when it was a scattering of large country houses along a road with distant views the Thames over fields, before the railways arrived and changed everything. Born in 1828, her brother was Thomas Hughes, who wrote Tom Brown’s Schooldays. She married at 18, and lived with her husband John – a not-very-successful Barrister – at Elm House, a country villa with a small wooded estate that sat on the current site of Battersea Arts Centre, and which is still remembered in the name of one of the rooms there.

Jeanie was the first female civil servant – ever! – becoming known as the first woman in Whitehall. She wasn’t just notable for this though – she was also a powerful social reformer, helping Octavia Hill in her work to build decent social housing management in Marylebone, and volunteering in supplying aid during the Franco Prussian war which was the forerunner of the British Red Cross. Following her work with impoverished children in Surrey, Jeanie was appointed Inspector of Workhouses, by the radical President of the Local Government Board James Stansfeld, and in 1875 she published a controversial report criticising the education of “pauper girls” – where the workhouse ‘Barrack’ schools seemed to lead to prostitution. This would have created some family tensions, as her father in law was the very man who had originally instigated the system of workhouses! She also argued for the fostering of all poor orphans, rather than their incarceration. She was ferociously attacked for daring to criticise the poor state of affairs, and her fight to defend her findings against male hostility politicised her, to the extent that she became an icon for the late 19th century women’s movement.

The painting of her above is by George Watts, who painted a series of portraits of the most important men and women of the day, intended to form a “House of Fame”. George said of Jeanie: when you read the biography of “That Woman”, for it is one that will be written, you will find she had very few equals. It took 130 years for it to be written – but it has now been written by Sybil Oldfield! There’s ongoing work to hopefully have a Battersea Society plaque to Jeanie on Battersea Town Hall.

Deaconess Isabella Gilmore, born in 1842, had been happily married to a naval officer, and looked set for a pretty normal middle-class life – until her husband died at 40. She then decided to train as a nurse – which caused a lot of misgivings in her wider family. Florence Nightingale had done much to improve people’s idea of hospitals, and nursing was seen as a worthy occupation – but was not really seen as something for an aspiring middle or upper class person to do, as hospitals were still considered too harsh an environment for well-brought up girls! But Isabella was adamant and she entered Guy’s hospital training school. Two years later took on as her own eight orphaned nieces and nephews when her brother died.

A further two years later, the Bishop of Rochester – clearly impressed by her industriousness – asked her to become a deaconess in his diocese, as part of a wider effort to revive the role of deaconess in the Church. Being a deaconess was quite a curious role – essentially being part of a ministry of women who would work among London’s poor and provide pastoral care, but reporting directly to the Bishop. Isabella didn’t have any theological training, and didn’t know much about the deaconesses either, but with some persuasion, agreed to go ahead. It seems she wasn’t hugely driven by the religious aspects, but saw a considerable opportunity to improve the lot of the poor of south London.

In 1887, she was ordained a deaconess – and with the support of the Bishop, built this in to an Order of Deaconesses within the Church – made up of women who were expected to be “a curiously effective combination of nurse, social worker and amateur policemen”. She set up a training house for deaconesses at 113 Clapham Common Northside. Getting hold of the building was an interesting challenge and shows her mix of pragmatism and ability to impress people with her dedication to the cause: she saw the house being emptied of its furniture as she walked across the common, following the death of its previous occupant, and found it had been bought by Thomas Wallis who lived nearby. She persuaded him to let the building to her, to house the new training centre. When Thomas died, she was able to persuade subsequent owner Herbert Shepherd-Cross – who conveniently happened to be an old friend – to sell her the freehold; Herbert even contributed £100 to her £4000 purchase price.

Isabella served actively in the poorest parishes in South London until her retirement in 1906, addressing the needs of the poor through working with girls and women. It wasn’t an easy life for her, or the deaconesses she trained at the house on Clapham Common: many left as the job proved challenging, not so much ‘dishing out alms to the poor’, but instead a lot of ‘real’ work. Gilmore insisted that the women were trained in basic theological principles, to be ready for parochial duties, as well as basic nursing skills (with some given the opportunity to train for six months at Guy’s hospital where Isabella had trained as a nurse herself). They provided a soup kitchen, donated clothing, looked after the sick, and taught religion and basic sanitation. Her older brother William Morris – famous in his own right as a social activist and major figure in the Arts & Crafts movement – observed that whilst he preached socialism, his sister actually practised it. The women she trained were paid, she was not.

Deaconesses paved the way for the ordination of women. There is a sculpted plaque to her memory in Southwark Cathedral. The house by Clapham Common, which is still standing at the corner of Elspeth Road (but now split in to flats) was later named Gilmore House in her honour.

Isabella personally paid for the chapel at the site – which features this rather fine stained glass window. The chapel was notable for its ‘Arts and Crafts’ style architecture (something we don’t see much of, which also features in our post on Battersea reference library), and the high quality of its fittings, mostly designed by Webb or Morris & Co (the firm Isabella’s brother William Morris ran). Though the chapel is still standing, it was stripped of most of its furniture in the 1970s for use as a recreation hall for students, and in the early 2000s was converted to a rather luxurious studio apartment – the photo below shows it just before that conversion took place.

Marie Spartali lived directly opposite Gilmore House, at about the same time, in a still-standing house called The Shrubbery (a very grand house on Lavender Gardens that just doesn’t look like it fits in Battersea!). Born in 1844, she was British Pre-Raphaelite painter, arguably the greatest female artist of that movement. During a sixty-year career, she produced 170 works, contributing regularly to exhibitions in the UK and the US. She studied drawing and painting under Ford Madox Brown. She painted images of active, empowered women that challenged the male gaze.

Marie sat for numerous paintings by Ford Madox Brown, Burne-Jones, Whistler, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and for photographs for Julia Cameron, and was a close friend of William Morris (whose sister Isabella worked next door). She married an American widow William Stillman, with three children and had three more. He was foreign correspondent for The Times resulting in them dividing time between London, Florence, Rome and US. She was described as “austere, virtuous and fearless, she was not lacking in a caustic wit and a sharp tongue”.

Marie worked in a period in which the opportunities for women artists were limited, and when social convention viewed them only as amateurs. She was, however, determined to forge her own career and created a significant body of work – over 150 painting in five decades – including The Enchanted Garden of Messer Ansald below. Her work is now regularly included in exhibitions about the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

And Marie is the first woman to have an English Heritage Battersea blue plaque in her honour! As art historian and Blue Plaques Panel member Andrew Graham-Dixon said, there are only a handful of female artists commemorated by the blue plaques scheme, and Marie Spartali Stillman is actually the first female Pre-Raphaelite artist to receive one.

Charlotte Despard was born the same year as Marie in 1844, into a wealthy Anglo Irish family. She married Max Despard and wrote ten novels.

Unfortunately Max died at sea in 1890, after which Charlotte wore black for most of the rest of her life. Charlotte was shocked and radicalised by the levels of poverty in London – and following suggestions by her friends that she could take up charitable activities, she devoted her time and money to helping the poor of Battersea. Nine Elms in particular had become criss-crossed by railways and industry by then, with more than its fair share of poverty and people very much on the breadline; Charlotte lived in Nine Elms during the week (at No. 2 Currie Street – a road which has completely disappeared and is roughly where the US embassy’s security screening section now stands) and created what became known as Despard Clubs. These were a forerunner of future community centres – and included a health clinic, youth and working men’s clubs, and a soup kitchen for the local unemployed.

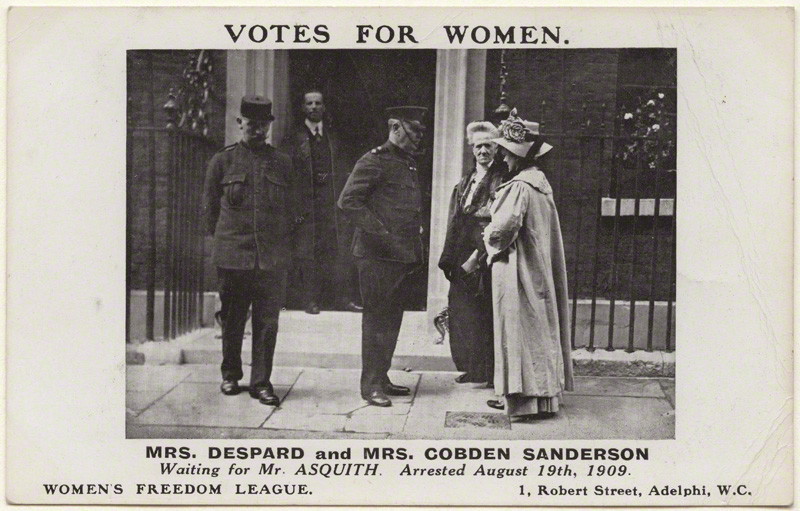

She was also a powerful campaigner. She became a member of the Independent Labour Party, and later joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women’s suffrage, and maybe better known as the suffragettes. Its members became known for civil disobedience and direct action. and Charlotte served more than one prison sentence! Sylvia Pankhurst, who was imprisoned with Charlotte, later remarked at her death that ‘She was one of our most courageous and devoted social workers. When I was in prison with her in 1907, I was impressed by her truly magnificent courage.’

Divisions started to emerge in the sufragette movement, and Charlotte left the movement (along with 70 others) to set up the Women’s Freedom League, a non-violent organisation – where she edited its magazine The Vote. She was an active member of the Battersea Labour Party and stood as the Labour candidate for Battersea North in the 1918 general election – but her anti-war views proved unpopular at the time.

After the first World War she left to live in Dublin, to campaign for Irish Independence – and clearly made an impact there too as she was classed as a dangerous subversive under the 1927 Public Safety Act for her opposition to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. She remained actively political well into her 80s and 90s: her house in Dublin was occasionally raided by the authorities, but a few years after she joined the Communist Party in 1930 it was burned down by an anti-communist mob! She died in Belfast in 1939, aged 95; recognising her extraordinarily sustained and varied campaigning her biography was titled “An Unhusbanded Life: Charlotte Despard, Suffragette, Socialist and Sinn Feiner“.

Charlotte donated a building to the Battersea Labour Party, and close to a century later 177 Lavender Hill is still their headquarters, with a plaque in her honour visible in our photo. Charlotte Despard Avenue in the Doddington & Rollo Estate is named after her, as is a both a street and a pub in Archway.

Hilda Hewlett, born in Vauxhall in 1864, was a pioneering aviator, and the first woman to qualify as a pilot in the UK. She attended the National Art Training School in South Kensington, specialising in skills which served her well in her later aviation engineering career: woodwork, metalwork, and needlework. She was also an early bicycle and car enthusiast – she learned to drive, took part in several car rallies, and was even fined for speeding in May and June 1905!

She attended her first aviation meeting at Blackpool in 1909, and then travelled to France the following year to study aeronautics, where she met aviation engineer Gustave Blondeau – and struck up a long running business partnership. She was clearly keen – and returned to England with a Farman III biplane! Within months, she and Blondeau opened the first flying school in the UK in Weybridge. Thirteen pupils graduated from the school in the year and a half it operated – with an impressive and unusual record of no accidents. the next year, Hilda became the first woman in the UK to earn a pilot’s licence. She taught her son Francis to fly too – he qualified as a pilot the same year; he went on to have a distinguished military aviation career, making him the first military pilot taught to fly by his mother.

Hilda’s role was to grow still more important as the first World War approached. and the need for aircraft became urgent. In 1912 in she, with Gustave, formed Hewlett and Blondeau, the first company to build Caudron aircraft in Britain – which they did under license from the Caudron firm, who were one of the earliest aircraft manufacturers in France. She forged straight in to setting up a factory – which she based in a disused ice skating rink called The Omnia in Battersea, which had seen all manner of unlikely uses in between including a car factory and a snooker hall. They eventually produced ten different types of aircraft.

There wasn’t really space for a fully fledged military aircraft production line in inner-city Battersea, so in 1914 she and Gustave developed a new factory in Bedfordshire specifically to build Farman aircraft. They named the new factory The Omnia Works to keep the Battersea link. They bought the land in May, and when the First World War started three months later the factory was able to meet government orders for aircraft for the wartime expansion of the Royal Flying Corps.

The Hewlett & Blondeau factory employed around up to 700 people at its peak (over 300 of them women), and produced more than 800 aeroplanes; after the war it diversified to make farm machinery but was eventually sold. Recognising the impact of the company she co-founded on the war effort, a road in Luton, Hewlett Road, was named after her. She emigrated to for New Zealand in the thirties, aged 66 – attracted by the outdoor life but still with a keen interest in flying.

English Heritage’s blue plaques may be male-dominated, but Jeanne Rathbone and the Battersea Society are filling the gap by doing a sterling job of filling the gap – with an ever-growing set of plaques to commemorate notable Battersea residents, in particular the women who have been under-represented in local and national commemoration schemes. The street view above shows one of these plaques at 4 Vardens Road, a quiet side street a few blocks west of Clapham Junction – which believe it or not was the site of the old ice skating rink that became Hilda’s first aeroplane factory!

This is the first of what will be a short series of posts on the women of Battersea. We’re deeply indebted to Jeanne Rathbone who developed most of the content of this article – and who has been a driving force behind telling the story of the many inspiring women who have made their lives and careers in Battersea. Jeanne is also a woman of many talents, among them local historian, comedian, one time Council Women’s Officer, former alcohol counsellor, humanist celebrant, and author of Inspiring Women of Battersea (available to buy for under £10 here – it’s well worth a read!). She has published far more detailed accounts than we cover here, and run several Notable Women of Lavender Hill walks. And with impeccable timing, Jeanne is leading a free walk on Sunday the 6th August, starting at Battersea Arts Centre then walking down Lavender Hill to The Falcon looking at sites and survivors of our most iconic buildings and plaques to women – registration details here.

Sticking with the theme of blue plaques, Hilda’s story isn’t the first piece of Battersea’s aviation history we have written about: a previous lavender-hill.uk article tells the story of how a smelly alley behind some bins near Battersea Park started a venture that became a major part of the UK’s aviation industry. Our series of local history posts also include an article about the interesting story of John Archer, the first black Mayor, who saw an English Heritage plaque installed in 2013.

Really appreciate this fascinating article about the hidden histories of remarkable Battersea women. So enlightening and inspiring. Thank you Jeanne and looking forward to more!

LikeLike

Pingback: The surprising history of a smelly alley behind some bins near Battersea Park | Lavender-Hill.uk : Supporting Lavender Hill