A few months ago we wrote about a rather unique house, hidden away between the big Victorian houses along the north side of Clapham Common. 64 Clapham Common Northside is much smaller and simpler building than its neighbours. It also looks very forgotten, with boarded-up windows, a neglected garden, and a hole in the roof.

This small house was built in the 1780s, and belonged to John Cunningham (whose son, also called John, was the Curate for Clapham, and later became the Vicar of Harrow). This was a time when Lavender Hill was a country track winding its way through the fields, on a hill overlooking the Thames valley, and Clapham Common was mainly used for grazing animals. However change was on the way, as wealthy folk started to build big luxurious houses with extensive gardens, making the most of the omnibus services that started to reach all the way out here from London. Many of these early houses clustered around the edges of Clapham Common, and a few along Lavender Hill (including Rush Hill House we’ve written a more detailed article on).

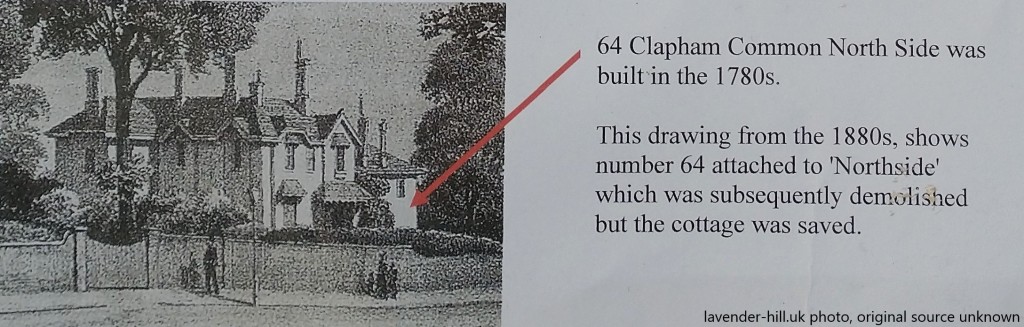

John followed the example of his new neighbours, and built his own big country house, called Northside, which was was finished in 1811. Unfortunately he within a year of the work finishing, so didn’t really get to enjoy his new house! Maybe because he needed somewhere to live during the building works, the original 1780s cottage escaped being demolished, but instead got incorporated into the new house at its eastern end, as a kitchen and servants’ wing – as shown below.

The new house, shown above, went through a few owners, and later had a substantial extension, as well as a ‘Swiss chalet’ being built in the grounds. It was quite an interesting property, with a complicated layout including a Gothic hall and a dining room with a coved ceiling, and large gardens including stables. It kept being well cared for, with full redecoration in the mid-1800s – but in the 1870s the railway arrived at Clapham Junction, closely followed by enormous levels of dense residential development, as well as all manner of industrial projects – and nothing would ever be quite the same again.

As we saw with our detailed history of Rush Hill House a bit to the north, the last few big country houses were increasingly at odds with the sounds, smells and general urban feel of their new industrial and residential neighbours. People who could afford a big house like Northside would now choose somewhere much further away from the city, and the land these big old buildings sat on was increasingly worth more than the houses themselves. Northside put up a good fight, staying put all the way to the 1890s – but the end was inevitable, and it was put up for auction, and quickly demolished, to be replaced by the network of streets we know today.

Or mostly demolished. Because one small bit of Northside, the original two-storey cottage (the one that had been incorporated in to it as a servants’ quarters and dairy) was saved from demolition, for the second time! It became a small house, much as it had been before Northside was built, and got sandwiched between a pair of new Victorian terraced buildings around the Common. And well over a century later, it’s still standing – now known as 64 Clapham Common Northside. It’s the one peeking out behind the big weeping willow tree in our photo above. Numbers 65–79, the red brick terrace to the left, replaced the main house, but are still attached to the two storey cottage.

It’s a building that is familiar to many people who lived here in the 1980s and 1990s, as for many years No.63 right next door was the local doctors’ surgery – for much of that time run by Dr Dunwoody, who had also been MP for Falmouth and Camborne in the late 1960s, and Minister of Health, as well as an early crusader against smoking as the first director of the Ash group (‘Action on Smoking and Health’). He later moved the practice to the brand-new Stormont Road Health Centre on the ground floor of what’s now Antrim House.

In 1987 and 1988 the house had two more brushes with demolition, with a couple of planning applications proposing major reworking of the building, adding extensions galore and an extra floor, and turning it in to a five bedroom house. Both were refused on the grounds that extra floors would be an insensitive change out of character with the existing building, and that some of the changes would be insensitive to the adjacent conservation area. The owners at the time appealed against the second rejection, and lost.

At some point after that the house seems to have been abandoned – and left empty for over a decade. It’s in a sorry state now, and no longer habitable. But there’s bene a burst of recent activity as the house seemingly changed hands, and was put up for sale by Fresh Aspects Property, for offers north of a million pounds. It was billed as a potential refurbishment project – or alternatively as an opportunity to build a new home, and to help pave the way for buyers to the sellers applied for planning permission to demolish the building and create a larger replacement building, echoing the form of the existing house but with more windows, a balcony and an additional storey.

After escaping demolition in 1810, 1895, and 1988 – would this be the end for Clapham Common’s original cottage? Well, it turned out that this lowly cottage had a lot of friends in high places, and the planning application gathered a variety of objections from neighbours, as well as detailed correspondence from the Battersea Society, the Clapham Society, the Georgian Society, The London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, and The Council for British Archaeology.

The Clapham Society noted that after losing the late-1980s planning appeal the previous owners had left it to decay for a decades, despite the fact that an 18th century cottage in a prime position overlooking Clapham Common could achieve a good rental income – and the strange abandonment could have meant a loss in rent of over a million pounds, and leaving it empty in a housing crisis made it worse. The architect of the latest rebuilding proposal had evidently struggled to justify the replacement of the original house with a taller ‘pastiche’ replacement in their heritage statement, which had included the bizarre argument that knocking down the building and rebuilding something else “will contribute far more to its conservation than any attempt at renovation“; this was dismissed as ‘complete nonsense’. The Battersea Society had similar views – also commenting that it was deplorable also that no action had been taken on the proposal made in 1988 that the building should be locally listed, and suggested that this should be remedied in the next review of local listings.

The Georgian Society , who specialise in the protection of Georgian historic buildings, weighed in with serious concerns – noting that demolition would create significant harm to the building that had some historic significance, and that the loss of the building would also cause some harm to the conservation area. They noted there was work underway to list the building, and that failing that it should be locally listed, and were concerned about the lack of information provided int he proposals on the historic fabric of the building that was still present. The London and Middlesex Archaeological Society noted that the house is a unique survival of the former built environment within the Clapham Common Conservation Area from the late 18th century, and should be preserved.

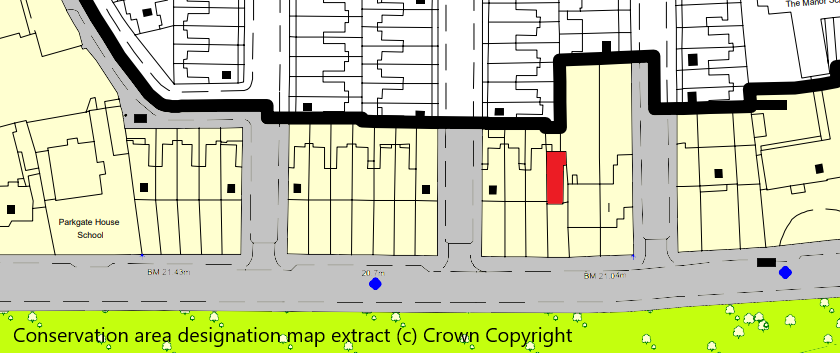

The Council for British Archaeology also opposed the demolition. In a strongly argued submission they noted that the modest scale of the building, its legibly historic character, and the phases of its evolution over time, illustrate the history of the development of the area and contribute to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area (which essentially covers the buildings along the side of the Common – No. 64 is in it, as shown in red in the map below). They noted that the rural and pre-nineteenth-century origins of Clapham Common were later largely hidden by nineteenth century development, and that the fact so little of that phase of the area’s development had survived gave this surviving cottage (which had also been a dairy, when there were still cows around!) particularly high historic value.

They described the Heritage Statement supplied alongside the application to demolish the building as “entirely inadequate”, strongly disagreeing with any suggestion that the lack of uniformity of No. 64 with neighbouring buildings as something that needed to be improved – pointing out that the different scale and style of 64 Clapham Common Northside was precisely what made it so important, and that this was key to the building’s historical value. This would be totally lost if the building was demolished and replaced with a pastiche copy of the later buildings in the area. They were especially concerned with the argument put forward in the Heritage Statement that the building’s demolition and replacement ‘would contribute far more to its conservation than any attempt at renovation’, saying that this “demonstrated a total lack of understanding of the significance of the scale, surviving historic fabric, and modest character of the historic building.” Its demolition would cause substantial harm to the historic building, which was the opposite of conservation. This was a damning objection letter, arguing that the application was wildly inconsistent with the requirements for a historic property in a Conservation Area.

This was a robust set of objections; we’ve reported on local development proposals for some years and we’ve rarely seen quite such a full house of comments along the lines of “you must be joking!”. But maybe the final nail in the coffin for these plans came from the Wandsworth Conservation and Heritage Advisory Committee, which met and discussed the case in some detail, and apparently unanimously objected to the demolition proposal, saying it was was unacceptable and entirely out of keeping with its surroundings. They noted that after the 1980s appeal was thrown out, English Heritage (now Historic England) had asked if the asset was wished to be listed, which was declined. There had also been a recommendation in 1988 that the asset should be locally listed. They noted that the house had remained empty for approximately 35 years, and thought it was ‘both shocking and bizarre’ that the property had been left in this state. Having confirmed that this was indeed an original Georgian building, and one that had remained remarkably close to its original condition, the committee felt was felt extraordinary that the property had not been Grade II listed in the way other similar buildings and structures had: it was “a rare case type”, as almost all of the other Georgian buildings had been lost across London.

By the time the planning officers got to the case, the conclusion was looking hard to argue with. And sure enough – permission to demolish and rebuild was refused. In their impressively comprehensive report on the case, they noted that the existing property makes a positive contribution to the character and appearance of the Clapham Common Conservation Area, and that the application had failed to clearly or convincingly demonstrate that the demolition was necessary to achieve public benefits that outweigh the harm from its loss. They also noted that because of its scale, siting and design, the proposed replacement building would appear incongruous, unsympathetic and visually intrusive, which would negatively affect the character and appearance of the Clapham Common Conservation area. It would also result in harm to neighbouring amenities in terms of increased overlooking, increased sense of enclosure and overbearing, loss of outlook, loss of privacy, and loss of daylight/sunlight. And that wasn’t all – the application had also failed to demonstrate how the new development could be done in a way consistent with the Council’s zero-carbon target. They also disagreed with the proposals to replace the current front garden wall with a much higher one going up to 2.3 metres: “front gardens and their boundaries are as much part of the public realm as the street and the common and that boundaries should not be so high as to obscure the building behind“.

Interestingly, the planning officers commented that the house was of considerable age and interest, and its poor condition did not undermine its historic interest. Noting it had been left empty for decades, they pointed out a note in current planning rules that says where there is evidence of deliberate neglect of, or damage to, a heritage asset, the deteriorated state of the heritage asset should not be taken into account in any decision – i.e. saying the building had ‘fallen in to disrepair’ was not an argument for demolition.

So the house has, yet again, survived! Like a cat, it somehow manages to defy death and keep going – but it has definitely cashed in a fair few of its nine lives by now, and after years of dereliction it’s already on the road to ruin, and it’s obviously not just going to stay as it is. So where do we go from here? Well the good news is that after a few decades of mouldering away, the building is in the hands of an active developer who’s clearly looking to do something with it. That ‘something’ is now unlikely to involve knocking it down, but it will likely include changes to extend it at the back, refurbish it to current standards, and generally address the sorts of issues you get when a house sits empty for decades with a hole in the roof. It’s an excellent location for a house, and there’s plenty of scope to turn it in to a real asset to its future owner as well as to Clapham Common. Local firm Fresh Aspects have successfully got several other ‘complicated’ buildings in the area back in to use, as we reported when we last wrote about this house, and there’s decent margin in refurbishing it or selling it on for someone to do as a project.

If this sounds like the project house for you – you’ll want to contact Fresh Aspects! If this was interesting you may also want to see our wider articles on local history, or on planning and development in the Lavender Hill area.