The 1880s were quite a big moment for Battersea. The railway had arrived, bringing with them an explosion of development – with houses, streets, entire neighbourhoods being built. There was a lot of money around, and everything and anything seemed possible. Which maybe explains how, for just a few years, we hosted our very own version of Crystal Palace.

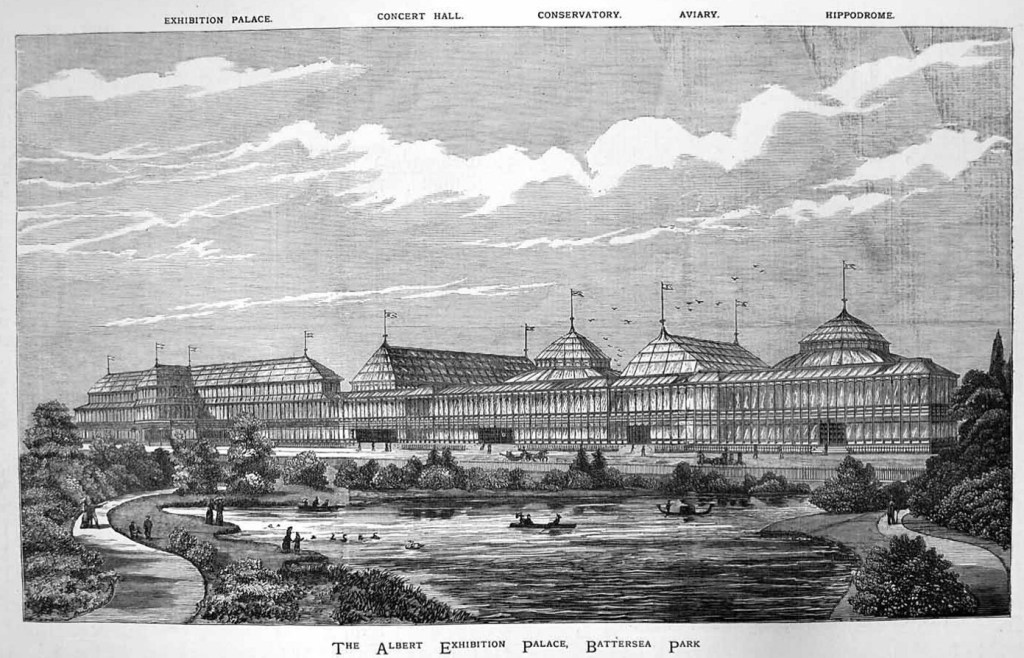

The Albert Palace, pictured above, was an enormous hall made made mainly of glass and steel, facing the south side of Battersea Park where the lake is, with its back facing Battersea Park Road. It had a vast central hall nearly 500 feet long, with space for displays and exhibitions, and a space designed to accommodate an orchestra. A separate concert room, the Connaught Hall, was attached at the western end. Even in the late 1880s no visitor attraction was complete without a cafe and gift shop, so the other end included a large tea room. All in, it was about half the size of the Crystal Palace, though a later phase was planned to extend it further.

It all came about because of an ingenious bit of recycling. This was a time when big exhibitions in purpose built buildings were very much in fashion, and one of them had been the Dublin International Exhibition of Arts and Manufactures in 1865, housed in a huge, but temporary, glass and steel structure. After the exhibition (which attracted nearly a million visitors) was over William Holland, a larger-than-life entrepreneur and entertainer who had successfully run several large venues including the Alhambra on Leicester Square and the Surrey Theatre in Blackfriars Road, spotted an opportunity to build something even bigger and more spectacular – a real People’s Palace. In 1882 he bought the whole building, dismantled it, and shipped it over the Irish Sea to be reassembled in Battersea. The Battersea Park site wasn’t a completely new choice either – it had originally proposed by Prince Albert for the relocation of the Crystal Palace itself after its run in Hyde Park ended (though it eventually made it to Sydenham).

The back wall, facing what’s now Lurline Gardens, didn’t look out on much so was faced with Bath and Portland stone. That was also recycled, but from a more local source – William bought the materials from the old Law Courts at Westminster, which were in the process of being demolished and replaced with the bigger and better Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand.

William Holland equipped the new Palace with a large garden to the south and west, which was designed by Sir Edward Lee, and included fountains, a conservatory and a bandstand. These included a children’s playground, and would typically see lots of events run in the day, including gymnastic shows, a diving bell, and ballooning (and it’s worth remembering that the site right next door was soon to become a hot air balloon factory, and one of the birthplaces of modern aviation, as we’ve written about previously). The north side also had planted terraces either side of the main entrance on Prince of Wales Road. Our sketch below shows the general layout, superimposed on what’s there now.

Although the new Palace was mostly made of recycled materials, this very much wasn’t a project done on the cheap, with considerable attention placed on getting the details right. As a sign of the level of intent, William brought in Christopher Dresser to design some of the interior of the new venue. He’s now widely known as one of the first and most important independent designers and a pioneer of the British Art Nouveau style, responsible for a lot of designs that were way ahead of their time (to the extent that some of his metalwork designs are still in production, such as his oil and vinegar sets and toast rack designs, now manufactured by Alessi).

There aren’t all that many surviving pictures of the interior. We have found one contemporary wood engraving, pictured below, from the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. It includes the organ, which had 4000 pipes and was one of the largest in the world, and the central hall (as well as some views of the Palace from the lake in Battersea Park, where the separate structure at the end housing the Connaught Hall is visible). This print is currently on sale at The Map House.

With everything assembled, William held the Grand Opening in June 1885, with a concert in the Connaught Hall, and about 5,000 visitors. Unfortunately it was a rainy day – so the main focus ended up being on the indoor exhibition stands, aquarium, picture-gallery, and numerous tea rooms, dining rooms and and bars. The Times reported on it in June 1885:

OPENING OF THE ALBERT PALACE. Despite the bad weather, which probably kept many would-be visitors at home, a large number of persons found their way to Battersea Park on Saturday, for the opening of the Albert Palace. The Palace is a handsome glass building of the Crystal Palace type, standing in extensive and prettily-laid out grounds, of which however the rain on Saturday prevented the public from making more than a cursory inspection. The interior of the building – a large nave surrounded by a gallery, which already contains the nucleus of a collection of pictures – is filled with models representing industries, cases of stuffed animals, among which a couple of splendid crocodiles from the Nile are particularly noticeable, and stalls for the sale of various articles, useful, ornamental, and indigestible. The exhibits as yet incomplete, as is but natural, but among them the beauty of several perfect river gigs and canoes seemed to attract general sympathy and admiration. Scattered here and there about the building are numerous refreshment buffets, tea stalls, &c., and there are several dining rooms, both in the building and in the grounds. This [refreshments] department is in the hands of Messrs. Bertram and Roberts.

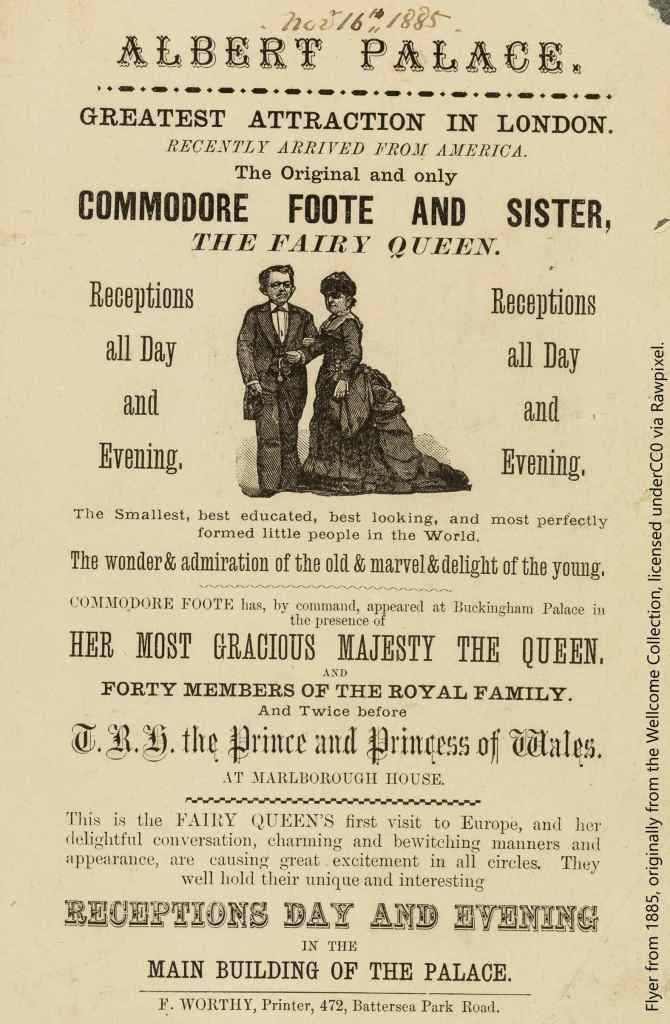

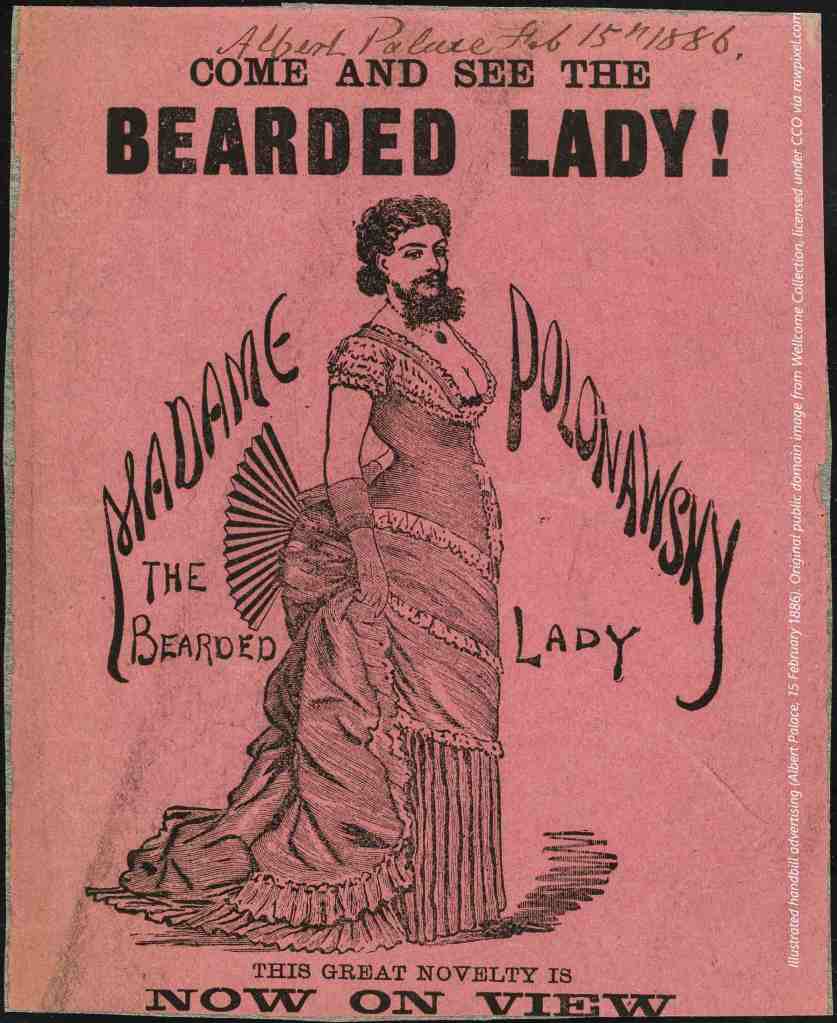

The following months saw regular concerts by the permanent orchestra and organist, who were joined by the Viennese Ladies Orchestra. There seems to have been a bewildering range of attractions including cat, bird and flower shows, and all manner of novelties including appearances by a ‘Giant Baby’! The Hall was also used as a general exhibition hall, conservatory, concert hall, aviary and hippodrome.

In one of the stranger promotional ventures, Arthur Lasenby Liberty, trader and the founder of Liberty’s department store on Regent Street, tried to bring a taste of India to Battersea by building an Indian Village inside the venue, complete with 40 silk spinners, weavers, carpet makers, metal workers, sandalwood carvers, embroiderers, a sitar maker, singers, dancers, jugglers and snake-charmers he had brought to the UK from India.

The original programme below for a day in April 1886 is maybe more typical of what was on offer. There’s a mix of entertainment from noon that the crowd could explore alongside the many exhibits and food and drink options, leading on to a general variety entertainment show in the early evening. The picture gallery includes Views of Old London, and a Collection of Modern Paintings. At 1pm and 6pm there are organ recitals in the Connaught Hall, at 2pm there’s a military band, at 5pm there’s a trio of Canadian skaters at the west end of the nave, but the main event kicks off at 7 with bands, jugglers, comedians and comediennes and dancers, equilibrists, French chansonettes, gymnasts, acrobats, character vocalists, and (in a sign that this was 1886) what are described as “American Negro Performers”, all wrapped up at the end by the Palace Band and a rendition of the National Anthem.

The programme – which has a picture of William Holland on the cover – also advertises steam boat fares from pretty much every pier in London, with tickets including admission to the Albert Palace. It also notes that there’s a well equipped reading room with all the daily papers, with arrangements to dispatch telegrams, as well as a everything you’d need to write letters (hopefully telling people how great the Palace is) and a postbox with five collections a day. This programme is currently on sale at Michael Kemp Bookseller if you’d like to own a bit of almost forgotten local history, and a similar one is on display until February 2025 at the London Archive in Farringdon (in an exhibition with free access).

The back page of the programme sets out the future events, including all manner of concerts, a series of Grand Firework Displays, a Temperance Fete featuring Old English Sports and Pastimes, a Grand Bicycle, Tricycle and Athletic Exhibition and Races (accompanied by a meeting of the champion cyclists of Great Britain). In May the outdoor illuminations of the site would be opened, and the site would offer balloon ascents.

It also sets out the future plans to develop the Palace and its entertainment offer further – with a considerable enlargement of the Fine Art Galleries, a series of flower and fruit shows (including a strawberry show and feast), a show of domestic pets (which included a category for poultry as well as the more obvious dogs, cats and birds), and a plan to build a grand circus in the grounds ‘in which high class entertainments shall be given, similar to those originated and so successfully produced by Mr William Holland, during the last two winter seasons at Theatre Royal, Covent Garden’. William also planned to develop a spacious billiard room with three tables, and to further develop the children’s playground.

It also confirms that ‘The palace and grounds will be magnificently illuminated by the electric light and gas, with, in extra Fete days, myriads of variegated Japanese lanterns and oil lamps’. The electric lighting was implemented in 1888, but this led to more than a few headaches for William as the place he bought the lighting from (the Jablochkoff and General Electricity Company) had a design that was suspiciously similar to the lighting that had been patented by their rivals the Edison and Swan United Electric Light Company. The latter took both William and his supplier to court, they lost the case for patent infringement but did secure an injunction preventing further use of the designs.

It caught the popular imagination at first, and regularly saw over 20,000 visitors on weekends. But problems quickly emerged. One of the bigger headaches was that the palace was expensive to visit, compared to the large – and, importantly, free – park next door. William had bet everything on attracting people from all over south London, in much the way that Battersea Park itself was already attracting crowds – but while the visitors certainly came, they did so in insufficient numbers to cover the huge costs of running the vast venue. Finances became strained, and in 1888 – just three years after it opened – it closed.

William Holland, as the owner and manager of the Albert Palace, lost £30,000 on the venture, a staggering sum at the time. He’d thrown everything at this hugely ambitious venture, and its swift collapse must have hurt. But he was clearly born and bred a showman, and he didn’t give up easily. He moved north and went on to undertake a significant redevelopment of the Blackpool Winter Gardens. Using what remained of his personal fortune he first stepped in save the theatre from bankruptcy. Armed with a motto of Give ’em what they want!, he then went on to become one of the greatest managers in the history of the Winter Gardens. With three decades of theatre management under his belt, and a huge contact book, he introduced the same eclectic mix of Victorian Variety that had proved popular in the summer programmes of the London music halls he had managed, aiming to offered a sense of upmarket luxury to all classes. Ever the showman, he became well known for his stunts to draw the crowds, including placing parrots in strategic places around the town trained to advertise his latest must-see attraction. He redesigned the gardens to include an opera house and a ballroom, while also rethinking its target clientele to cater for the working class demographic, with an all day admission price and fixed ‘one shilling dinner’ that proved very successful.

The now-empty Battersea building, meanwhile, faced an uncertain future, as it got tangled up in legal disputes. It had become a popular local landmark and many tried to save it, with the Vicar of Battersea heading up an Acquisition Committee. But this would be complicated as any buyer would have to take it subject to the lease which, technically, still belonged to the original developers – the Albert Palace Association. That company was now in liquidation and taking the lease on would mean taking on a lawsuit.

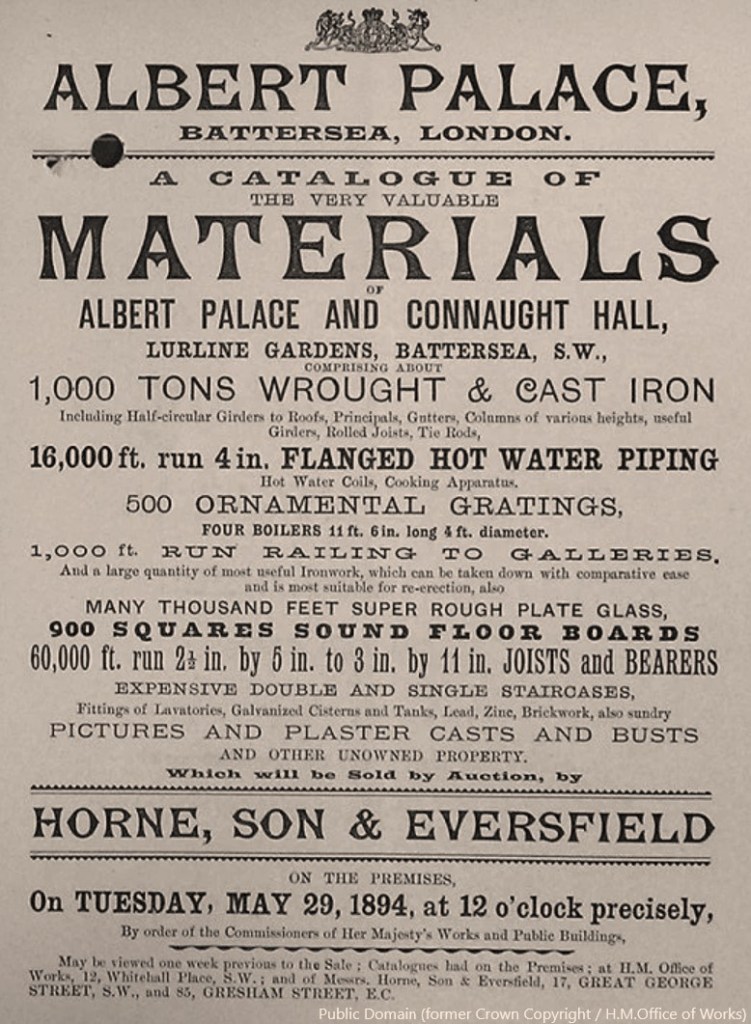

So the grand palace, installed just a few years earlier, slowly decayed and became a ruin. Many of the once spectacular windows were broken and pigeons started to take over the interior. It was finally demolished five years later, with the entire contents of the building put up for auction in 1894 including wrought and cast iron, piping, ornamental gratings, boilers, toilets, bricks, plate glass, joists and beams, staircases, pictures and plaster casts. The grand organ, one of the largest in the world with its 4000 pipes, survived and eventually ended up in Fort Augustus Abbey in Scotland, where – having been electrified and reduced in scale to fit a more normal sized building – it’s still working.

The cleared land was then leased to a local developer, C.J. Knowles, who we’ve written about before as he also developed the original houses along Cedars Road. Mr Knowles had wanted to get hold of the land for some time, initially to build large villas. There was less land available now, so to make the sums add up he instead developed a series of tall mansion blocks facing the park.

Albert Palace Mansions and Prince of Wales Mansions now stand on the site of the Palace itself, while its adjacent pleasure gardens became York Mansions. The new mansion blocks were designed to recreate the splendour of similar buildings north of the river in Chelsea, and attract a higher class of resident. It seemed to work – the mansion flats with their commanding views over the park were a new type of residence that was taken up by modern thinking people with comfortable incomes, while the traditional housing nearby were increasingly shared by multiple families of more limited means. A somewhat intellectual and artistic community developed there from the outset which was alluded to in a short story by P.G. Wodehouse (The Man with Two Left Feet) and a novel by Philip Gibbs (Intellectual Mansions S.W.). Blue plaques commemorate authors G.K. Chesterton and Norman Douglas, playwright Sean O’Casey, and artist Charles Sargeant Jagger.

One bit of the pleasure gardens was converted into the Battersea Polytechnic, pictured below, which opened in 1891 to give poorer Londoners access to higher education. It became the Battersea College of Technology, and in 1966, when the college became the University of Surrey, it moved away to Guildford and the building has since then also been converted to flats.

William Holland died in 1895, in his late fifties. The Globe penned a short obituary, which noted that the Albert Palace had ended up as a rare failure on an otherwise successful career: ‘A prominent man the world amusement has passed away by the death of Mr. William Holland at Blackpool yesterday. For many years he was connected with London places of amusement, including the Alhambra, the Surrey Theatre, the Royal and Canterbury music-halls, and the Albert Palace. The last-mentioned was an unpleasant experience for him, as he lost £30,000 there. To recoup his fortunes he went to the Winter Gardens at Blackpool, which he made one of the most attractive places of resort in the North. He was born 1837; his early experiences, like those of many other entertainers, was as a travelling showman.’

The Albert Palace lives on in the name of one of the mansion blocks, but today it’s just another quiet street near the park. There’s very little sign of the drama and excitement that the site once had, when it was one of London’s top entertainment venues. If William’s big project had survived, chances are this bit of Battersesa would have been a very different place.

This is part of an occasional series of posts on history of the area round Lavender Hill in Battersea, London. To receive email updates on new posts sign up here. Our local history articles are here; including posts on how this bit of Battersea was where the UK aviation industry started, on the pioneering women of Battersea’s early days (who included factory developers, social reformers, fearless pilots, celebrated artists, tenacious campaigners and ‘dangerous subversives’), and on the grand plans that could have seen a much smarter and more expensive bit of London built along the Queenstown Road. For more on the Albert Palace you may wish to see Chris Van Hayden’ article here, an article by the South London press here, or Battersea Banter’s post here. Thanks also to the team at The London Archive which is where we first found out about this bit of Battersea history.