Work your way through the 1950s Notre Dame housing estate at the Clapham High Street corner of Clapham Common, and after going past a load of bins and a few rows of decaying garages, a rather decent children’s play area emerges – with a zip wire, swings galore, small climbing wall, table tennis and even a rarely-seen teqball table. More unusually, at the back of it, stands a Georgian-era colonnade that seems to have walked straight out of a Turner painting.

It’s the Clapham Orangery – and it dates back all the way to Clapham’s long-lost days as a cluster of large country houses scattered around the Common. Thornton House was a particularly big house whose garden stretched all the way to what’s now Abbeville Road, included the whole of what is now the Notre Dame Estate (and because that includes a load of terraced houses as well as the more recognisable big blocks of flats, that’s a huge garden). The house was built by John Thornton, a man of considerable means, and Director of the Bank of England, who was said to be the second richest man in Europe.

The house was inherited by his youngest son Robert – also a wealthy man mainly thanks to a huge £40,000 inheritance from his dad (well north of £5 million in today’s money). Robert would become an MP, and director of the East India Company. He was clearly popular wherever he went, described as ‘a most agreeable, lively and pleasant man’ – and he was also known for having a large collection of prints and minerals, and a real love of plants. The huge garden was clearly no accident – the gardens of Thornton House were described at the time as ‘the most expensive gardens in the vicinity’ – including stables, parkland, meadows, a grotto, and woodland. To make a central feature, in 1790 Robert built ‘an exquisite greenhouse’, strategically placed by the side of a long ornamental lake, with grassy banks and overhanging trees either side.

It’s not really a greenhouse as we would imagine them now, more a grand stone orangery that had glazed sides facing south/south west to catch as much sun as possible, with an interior suitable for a variety of exotic plants and trees – including, no doubt, orange trees. Spelt out over the door is HIC VER ASSIDUUM ATQUE ALIENIS MENSIBUS AESTAS, roughly translating as ‘Here is persistent spring, and in months where it should not be, summer’, topped by a floral garland made of locally-developed Coade stone. It was also a social space: the Thorntons hosted Queen Charlotte at the orangery in 1808.

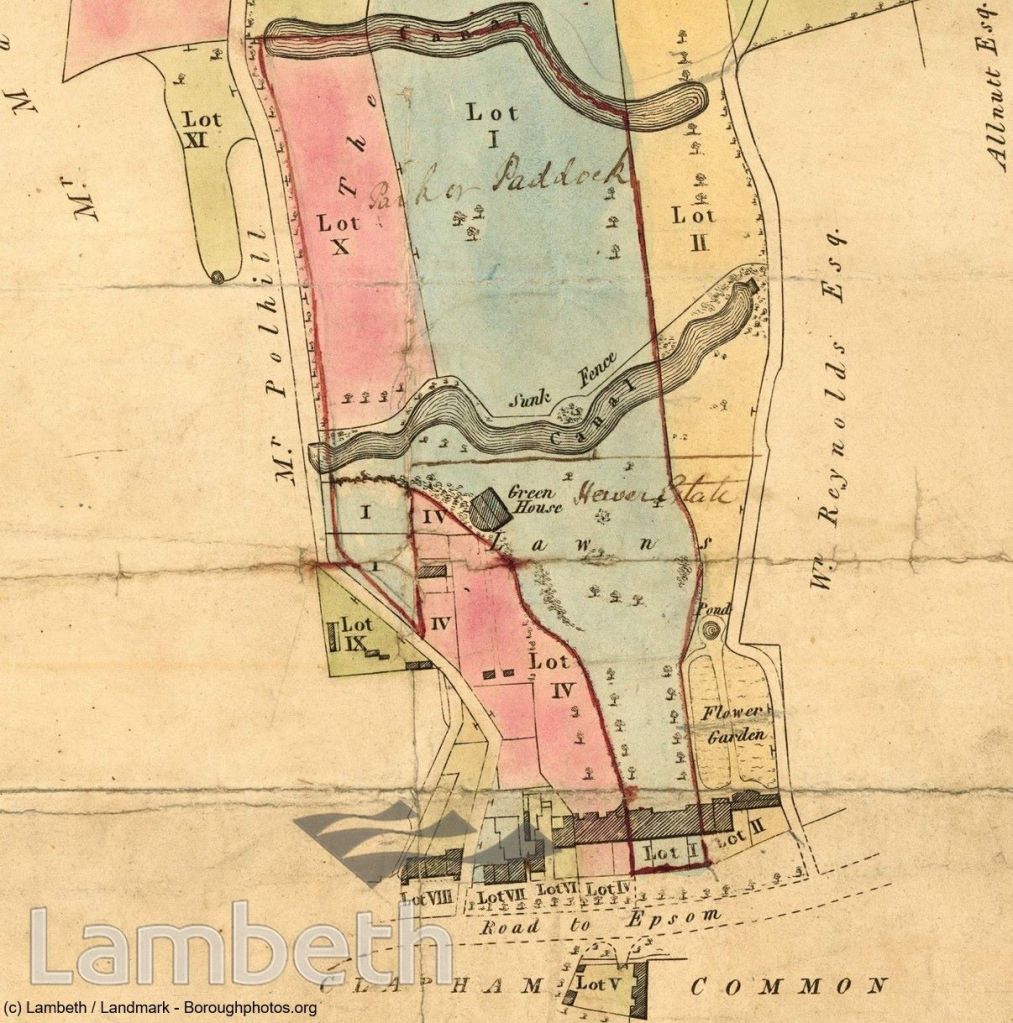

Robert’s impressive 13-acre garden was a real landmark and the talk of the town, but his business ventures didn’t go so well. He had some early success in investments, but later made some large stock market losses, while his business got tied up in the politics of the time and lost a lot of value. Having gone from being a very wealthy man to being £45,000 in debt; he put the house up for sale by 1810 – the map above shows the way it had been split in to individual lots with the orangery labelled ‘Green House’ in the middle of the blue section, placed in a way to have sweeping views along one of the two lakes in the gardens. Selling the house didn’t end Robert’s financial woes, he ended up bankrupt and fleeing to France in 1814 under a false name to escape his creditors, later moving on to the United States where – still a popular figure with his neighbours, if no longer a wealthy one – he died in 1826.

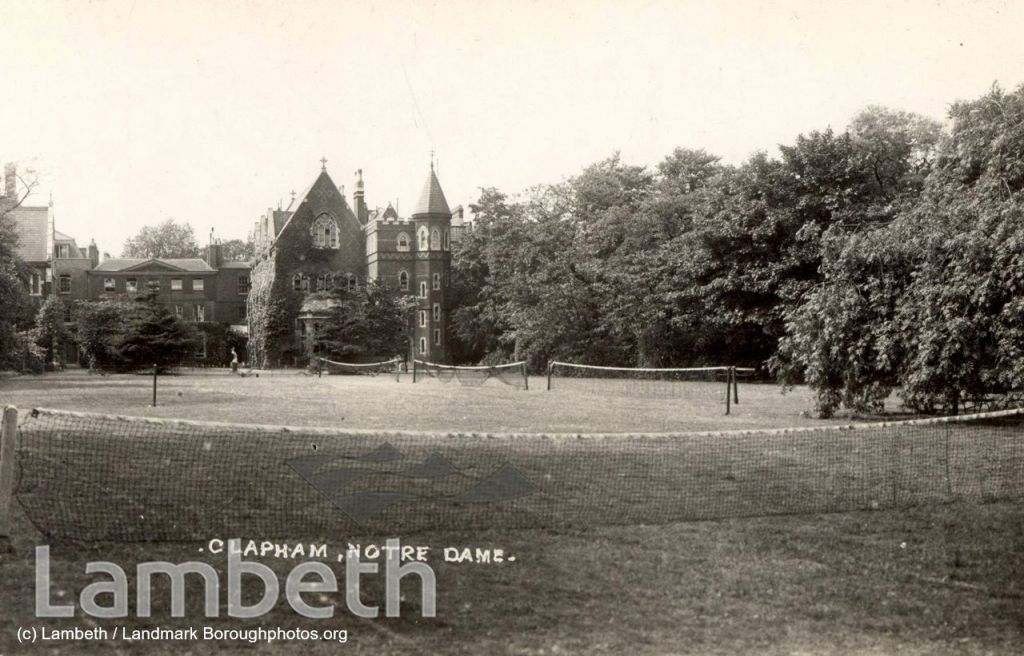

But his house and gardens mostly carried on: the pink and blue sections stayed in common ownership, with the end further way from Clapham Common split off – with the second lake filled in and becoming part of Abbeville Road. In 1851 most of the estate was sold to a convent of Belgian nuns, the Sisters of Notre Dame, who developed a network of religious schools around the country. They had a clever, and innovative for the time business model of establishing fee-paying day schools (and sometimes boarding schools) for young ladies, which would provide them with an income, and using the income to open separate poor schools or work in established parish elementary schools; they would also develop the Notre Dame school in Battersea. They established the Notre Dame convent and girls’ school on the site. They kept the house, orangery and lake – but added new buildings, playing fields and tennis courts, and the girls could row on the serpentine lake and ride ponies in the grounds.

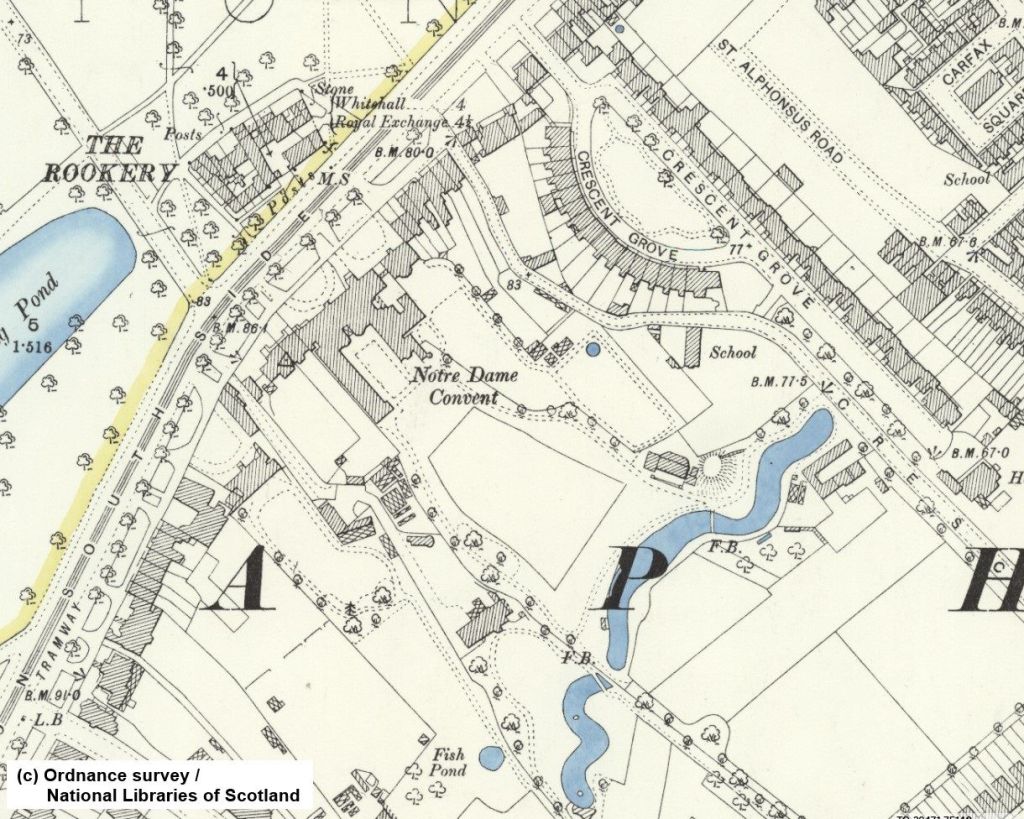

Thanks to National Libraries of Scotland’s brilliantly structured collection of historic maps we can see the layout of the convent, with one lake still in place and the orangery still standing as the grey building just above the large ‘P’ of Clapham:

The school ran happily for decades, until in 1939 the sisters left – as the whole school was evacuated to the countryside after seeing some damage from German incendiary bombs. We’ve seen reports that the empty accommodation at Thornton House was then requisitioned by various government Ministries, with the Free French Forces, Charles de Gaulle’s resistance government in exile, moving in for several years. By 1945 the once spectacular house and gardens were declining: the glazing on the orangery had been destroyed, and the house had taken blast damage.

After the war the school returned, but in a different location in Clapham; the nuns sold the property – to the local Council, who had a pressing need to build a lot of new housing in a hurry. This was a time when development was unusually ruthless, and the next years would be brutal for Thornton House: both the house and the later school additions were summarily destroyed, Robert’s prized trees and plants were bulldozed, the winding lake was filled in, and a network of streets were laid out over the gardens. A new housing estate, designed by the borough of Wandsworth (as this was, back then, part of Wandsworth) and named after the Notre Dame convent, was developed – creating 400 houses and flats.

The estate design is, to be frank, not great: the architects’ main aim was to build as many flats as they could, as quickly as possible, while keeping the spend to the bare minimum, and compared to some of the very carefully designed estates Lambeth would build in the following decades (some of which we have reported on) it’s a fairly bare bones affair. But they did try to elevate it and make it a good place to live – working with what they had -which in this case, led them to save the orangery, and keep an area of land around it free of development, as a feature and as a central green space for the estate. The trashed windows had to go, but the rest was in serviceable condition. No longer within private grounds of the school, it became a more accessible local landmark.

Soon after the estate was developed, the orangery caught the eye of the authorities as a rare survivor of times long gone – and it was made a Grade II listed building in 1955. From then onwards it was a story of little change for decades – and as Lambeth went through its famous years of political activism and financial chaos in the 1980s, a late 1700s orangery was the sort of thing many in the Council really couldn’t care less about. It became very neglected and ended up covered in graffiti, with the drainage and some of the ornamentation falling off, and damp everywhere.

Following a sustained effort by the Clapham Society who have been trying to protect it for decades, a local group called the Clapham Orangery Group brought English heritage on board, proposing a preservation trust and offering funding assistance for repairs – “providing Lambeth demonstrate its commitment to its future and long-term preservation” (it’s clear that English Heritage didn’t have much faith in Lambeth either!). This did lead to the orangery getting repairs and being cleaned up – and Lambeth themselves got back on track, managing the estate as well as could be expected in the circumstances and keeping up with basic maintenance on the orangery.

But it still never had a purpose – so didn’t get much more than the minimum in terms of care and attention. The gradual decline of the structure saw it added to the Heritage at Risk list of buildings whose end may be near – where its condition there is described as ‘fair’, with reported ‘slow decay’ with no solution agreed.

However things have changed since Historic England’s website was last updated, to rather more rapid decay – as in early August a large part of the roof completely collapsed! As our photos show, it’s really not looking great – the whole structure has come down, and the top of the walls are now exposed to the winter. Security fencing has been put up around the building to keep people at a safe distance in case any more of the structure collapses.

The building is owned by Lambeth’s housing department – and they have other priorities. We’ve occasionally reported on the headaches facing Lambeth’s big estates, with looming maintenance nightmares increasingly on the radar as ageing and high-rise properties reach the point where a lot of their infrastructure needs substantial investment to keep things going, let alone bring property up to current standards – our article on the vexed question of what to do with the Westbury Estate, whose phased redevelopment has become severely stuck, and whose towers are increasingly looking to need major works, is here.

The Notre Dame Estate that completely surrounds the orangery may be another of these headaches – a hastily built complex that delivered a lot of flats on a particularly tight budget, much which – having been built in the late 1940s – is approaching its eightieth birthday! A centralised heating system with exposed pipes and ductwork covers missing, a questionable level of thermal efficiency, mediocre accessibility, and reports of recurring infestations of ants, are a very direct illustration of the financial demands Lambeth is facing with many of its high-density, high-rise buildings.

Lambeth’s also increasingly struggling to keep its head above water financially – just last week an auditor’s report set an ominous tone on the state of the Borough’s financial affairs, with concerns on almost every element. It may explain how we got to this situation in the first place (a cursory Google maps exploration shows that water has been pooling on top off the roof for some time – never a great sign!) – and none of the financial challenges augur especially well for their ability to get the building repaired any time soon.

On the plus side – the damage is so far limited to the roof having collapsed, and it’s not an especially complicated fix if it can be done fairly soon, before the walls and structure take further damage from their exposure to the elements. The flat roof, while fashionable when the orangery last saw significant works in the 1950s, was always going to be a maintenance headache, and a gently sloping corrugated steel replacement, coupled with a replacement suspended ceiling, is both more in keeping with the way it would have originally been built, and a better long term bet for the structure. The Clapham Society – who are still some of the key people trying to keep our orangery alive – report that Lambeth are seeking external funding to pay for repairs estimated to cost £100,000, and that the London Buildings Preservation Trust is in discussion with Lambeth about using its experience, skills and resource to save the Orangery.

The slightly isolated location of the orangery limits its ability to generate income to pay for its ongoing upkeep – so this isn’t going to see the original glazing between the columns restored and the building up for lease as a cafe any time soon, echoing what (as we reported) happened to the similarly imperilled old building in Clapham Common’s woods, and which could have been a very real option had the orangery been slightly closer to the Common. It used to be open as a play area, and has occasionally been used as a film location – but maybe the key is to find an ongoing use (and we’re interested if any of our readers have ideas that would be compatible with its listed building status).

Robert Thornton’s one-of-a-kind greenhouse has already done well to reach its two hundred and thirty fifth birthday, and we owe the designers of the estate some credit for sparing it from the bulldozer, as well as the team in the 1990s who rescued it. It’s now a lonely, broken and mostly forgotten local landmark, hidden in an ageing housing estate, surrounded by cracked paving and emergency fencing, and in the not-very-caring hands of a cash-strapped local authority. It’s all a far cry from its days as the treasured of a passionate plant collector, when it was surrounded by lush greenery, packed with even more exotic plants, and the talk of the town. Can it fight on, as one of the last reminders of the way Clapham was before it was taken over by London, and as something that makes the Notre Dame Estate a bit special? Or is this the beginning of the end? Fingers crossed a way forward can be found – and we’d encourage you all to do what you can to get this poor building the care and attention it deserves – and as ever, we’ll keep you posted.

Lavender-hill.uk is a community site covering retail, planning and development and local business issues, centered loosely on the Lavender Hill area in Battersea, with occasional more detailed articles on local history, and other subjects of wider community interest. If you found this interesting you may want to see recent posts on Battersea Power Station’s mysteriously missing historic cranes, on the story of how one of Clapham Common’s oldest houses was saved, or on the pioneering women of Battersea’s early days. You can also sign up to receive new posts (for free) by email – and if you have tips and leads to share, get in touch. There’s also lots more detail on the orangery, including a rare old photo of it when it still had the windows more or less in place, at the Folly Flaneuse.

Pingback: Clapham Junction’s Rough Sleepers Hub opens for business | Lavender-Hill.uk : Supporting Lavender Hill