In the next few weeks, small brown bins will appear all over the Lavender Hill area. Everyone in Wandsworth borough who currently has a front-door rubbish collection will get one – so they can use the new weekly collections of food waste from the 10th June. It’ll take a bit longer for this service to extend to flats (where the logistics of finding space in bin sheds can be quite awkward), but the plan is to roll out larger food waste bins to flats by the end of the year. You’ll be able to use these bins for any food materials – including pet foods, and anything biodegradable from food preparation, including inedible bits like bones, eggshells, fruit and vegetable skins, tea bags and coffee grounds.

Wandsworth’s also giving everyone a year’s supply of compostable food waste bin liners to use – using these liners will keep things cleaner and easier but is up to you. After then you’ll need to buy your own; they are sold at most of our local supermarkets; they do ask that everyone checks any more liners include the ‘compostable’ logo shown to the right.

This isn’t really something Wandsworth chose to do. National government has been trying to standardise rubbish collection arrangements for some time, to avoid the confusing situation where local authorities all collect a different set of recyclable products – in the hope that a more standard approach will be better understood, and push overall recycling rates above the current rate of about 44%. Under a new government plan every Council will have to collect a minimum range of recyclable products – which Wandsworth and Lambeth already do (indeed, they both go further than the minimum and collect other more complicated items like aerosols and Tetra Pak containers). Another new rule is a requirement for all Councils to collect food waste. This is old news to our readers in Lambeth, who have had similar brown bins for years (for houses, with plans to extend the service to flats) – but something new for Wandsworth.

An interesting question is – is collecting and recycling food waste a good idea from an environmental or efficiency angle? The evidence is mixed. It partly depends on how the waste is taken to wherever it is processed: if it leads to miles of driving by big diesel lorries round remote rural communities to collect tiny amounts of food waste, or long trips out to far flung waste processing centres, things don’t look great. But if fairly clean modern vehicles can be used (as is the plan for Wandsworth, which is currently replacing the whole fleet) and the distances travelled kept down (where a dense town centre helps – vehicles will fill up fast with not too much driving needed), it starts to look a lot better.

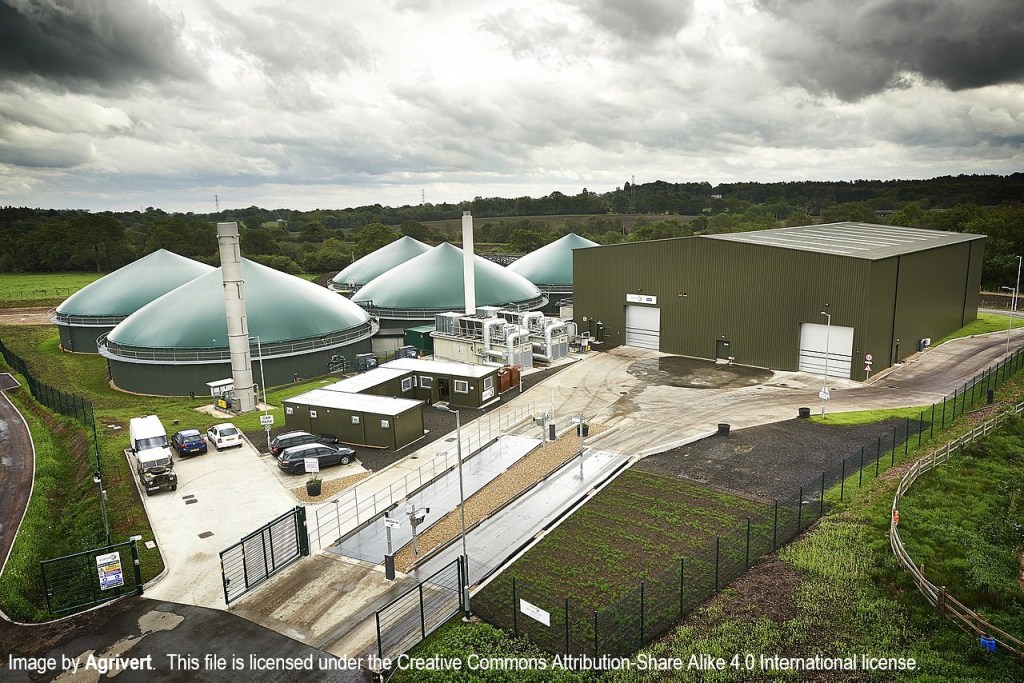

It also depends on what happens to the food waste at the other end. The best option is ‘anaerobic digestion’, which is quite a clever process. First the waste is mixed in with some water and heated up, to make sure that any notable dangers like E.coli from meat waste are eliminated, and filtered (to remove other waste and plastic (as try as we like, it’s very hard to avoid some contamination – and the same goes for recycling collections). It then goes in to a big digester, with a resident population of tiny bacteria. These bacteria are the heroes of the piece – over several weeks they will do the hard work of digesting the assorted bits of food – pretty much the same way as happens in someone’s stomach. As they do this they create heat (which goes back to be used in that killing-off-the-nasties stage at the start of the process), a sort of organic liquid fertiliser (which is sold off to farmers), and methane gas (which is collected off).

The fertiliser is an ingenious way to put a lot of carbon back in the soil rather than it being emitted (and also avoids the need for farmers to use manufactured fertilisers). The methane can, at least in theory, be put in to the gas grid – but building a new connection to the gas pipeline network, and installing all the kit needed to check it’s the right mix of gas and the machinery compress it to the right pressure, is a slow and expensive process (and hard to do even with the benefit of a government subsidy to anaerobic digesters that make gas for the grid). This means that almost all anaerobic digestion plants include mini power stations that burn the gas to make electricity, and sell that to the grid instead (as getting a connection to the grid is relatively cheap and quick).

Actually running one of these anaerobic digesters is as much of an art as a science! You need to get the precise mix of nutrients to keep all the little bacteria well-nourished and efficient, and to keep the temperature comfortable for them. Just like people, a good balanced diet keeps our digestion healthy – and sometimes keeping the digestion plant running means adding ingredients such as manure or other specific trace elements to the feedstock, and if you get the wrong mix of food waste you have to work hard to keep the process going – sometimes adding oatmeal in to give the bacteria a chance to recover with a bit of calm, bland food! You also need to give the bacteria time – as if you rush it the end product is a smelly mess rather than a nice clean fertiliser, and farmers find their lovely farm suddenly gets rather stinky, start getting complaints from the neighbours, and stop buying it. The way the plants are managed has a significant effect on the overall effect they have in reducing emissions – a 2022 research study found that of 30 plants in France that mostly processed agricultural waste, a decent number reduced carbon emissions compared to the more traditional approaches of muck spreading, thanks to careful recovery of all the heat produced, and careful design to avoid any methane leaks – but a fair few didn’t! But when you do get it right, it’s a really clever process that turns lots of waste in to nothing but useful products that can be sold – and ensures that the plant maximises the amount of useable energy recovered from the food waste, whether as heat, fertiliser, gas or power. The plant below is an example run by Agrivert, which recycles food waste from several London boroughs (image source / license).

There are other ways of dealing with this waste, the most common one being to compost it – and letting it decompose to make soil. It’s a simpler process and it will get rid of the waste, but it creates a fair bit of methane in the process, a troublesome greenhouse gas, which can make the overall benefits of collection more dubious. Newer technology has helped to reduce (but not eliminate) the methane involved – mostly by using composting containers that allow more air in to the compost as it forms.

Both of these approaches are arguably better than the current end use of this waste (which gets put on a boat and taken down the river to an incinerator in Belvedere, where it is burnt to create electricity – leaving nothing but ash and a small amount of metal and glass that got put in black bags rather than recycled). At this stage we don’t know what Wandsworth plans to do with the food waste, though the pilot programme a couple of years ago in Southfields used anaerobic digestion.

It does mean a more bins likely to be left on pavements – although food waste bins are small and portable, and Wandsworth has wisely given residents the choice of what (if any – bags also being fine) bin to use for the rest of their rubbish, in contrast to Lambeth next door where rubbish will only be collected from official Lambeth wheelie bins on many streets. Some Lambeth streets spend most of their time flooded with hundreds of somewhat oversized bins clogging up the pavements, sticking about pretty much full-time given there’s not really anywhere else to put them in streets where the houses have minimal front garden spaces. Wandsworth Road, above, maybe typifies this issue – where each house was assigned two large bins without really thinking about their gardens being small, unfenced and sometimes sloping ledges, up steep and angled steps, and the narrow pavement not being wide enough for safe pram / wheelchair access when it is covered in bins.

There’s one other new feature coming to Wandsworth’s rubbish collections (again, one already available in Lambeth): collection of small electrical appliances for recycling will start on the 10th June for many households who get a door-to-door waste collection, alongside the regular rubbish collection. By small, the Council means ‘up to 25cm’ – this isn’t a collection service for your old fridge! It seems that some sort of arrangement to recycle electrical goods is also on the way for flats – but this may involve collection points scattered around the Borough rather than specific bins in particular blocks. Some of these bins are already in place, like the one below (which is on Ashley Crescent). At some point in the next few years, recycling collections right across the country are also set to expand to include plastic film (like carrier bags).

All these new collections and the infrastructure to handle the waste that’s collected are not a cheap thing to organise. The government – bound by a well-established principle that if it imposes ‘new burdens’ on local authorities, it needs to fund them – has said it will provide funding to cover ‘all reasonable costs’ to councils that come from that this new recycling requirement – including bins, collection lorries, and possible plants to store and process the waste. However they are not actually telling Councils how much they will be paid, or when, and with a central government which is not exactly known for its love of London at the moment there’s a risk that Wandsworth may end up feeling short changed!

So – will this expansion of Lavender Hill’s recycling work? Food waste recycling seems to be doing reasonably well in Lambeth, though not a lot of data has been published on how much is collected overall and what impact that has on emissions. Wandsworth’s current overall recycling rate is about 25%, which is fairly typical for an inner London Council (where the average is 28%) but notably lower than Lambeth’s at 35% – so there’s plenty of room for improvement.

Experience elsewhere suggests some people will become very efficient food waste recyclers, and some won’t bother – but it should lead to a reasonably steady amount of useable waste being collected. We’ll have to see if Lavender Hill’s resident foxes learn how to open the bin locks to get to a good source of food, which has been a bit of a theme elsewhere (though early tests suggest that Wandsworth’s bins are a bit more robust than the ones that have been in use in Lambeth – and waste put out in these bins may be less tempting to foxes or crows than the same waste in black bags). Overall, this is potentially a decent move for the environment – making better use of our food waste, and reducing what goes in our black bags.